Includes score and parts.

Vapor Trails

1 movement. 7-8 minutes.

Vapor Trails in context

The use of computers in the production and dissemination of music has become a commonplace unworthy of note. As Nicholas G. Carr wrote in a notorious essay published in the May, 2003, Harvard Business Review, information technology no longer matters. It's not that it's not important, but its very ubiquitousness and indispensability to postindustrial society have rendered it a basic commodity, an essential layer of plumbing comparable in some ways to the electricity grid. Vital, yes, but a distinguishing characteristic capable of giving someone a competitive edge? No longer. Carr was speaking of the use of computers in commerce and industry, of course, but a comparable evolution has occurred in the creative use of computers in the arts. What was in the 1960's and 1970's an open-ended, speculative, and often clumsy effort by basement-dwelling computer nerds and iconoclasts to explore radically new sounds and new ways of organizing sound has matured in the twenty-first century into low-risk, technically superficial tinkering with the combinatorial possibilities of infinitely reconfigurable networks of powerful synthesizers and samplers. The results of this tinkering are often acoustically stunning and often inhabit the type of multi-layered, irony-laden pastiche beloved of the more superficial cadre of postmodernists, but something important has definitely been lost. Something rough, arbitrary, counterintuitive, contrarian, and a little naïve, but also honest, humble, and willing to deal with the unknown as something more than a tourist attraction. Pardon this lapse into the rhetoric of the American Frontier, but there's probably a connection here to be explored, for better or worse.

Between the mid-1970's and the mid-1980's the universal paradigm for writing, and using, computer systems changed from so-called "structured programming" (verb and process-oriented task analysis) to so-called "object-oriented programming" (noun and thing-oriented context analysis). It was this evolution in computing theory, even more than the spectacular increase in processor speed and memory size during the 80's and 90's, which had a profound effect on the nature of our engagement with digital technology in the arts. In music this change in the programming and user paradigm was reflected in a shift away from information theory, with its emphasis on creating streams of implication, surprise, deferment, tension, release, and the artful semblance of order in a world prone to chaos, and toward semiology, with its emphasis on the manipulation of an inherited repertoire of signs and its lamentable aversion to messy questions of meaning, or, heaven forbid, politics.

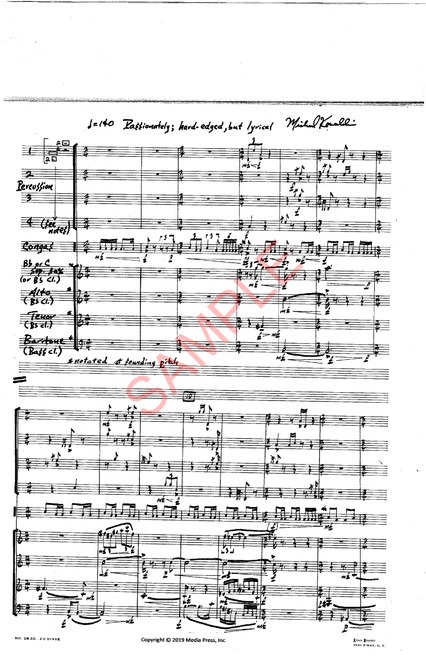

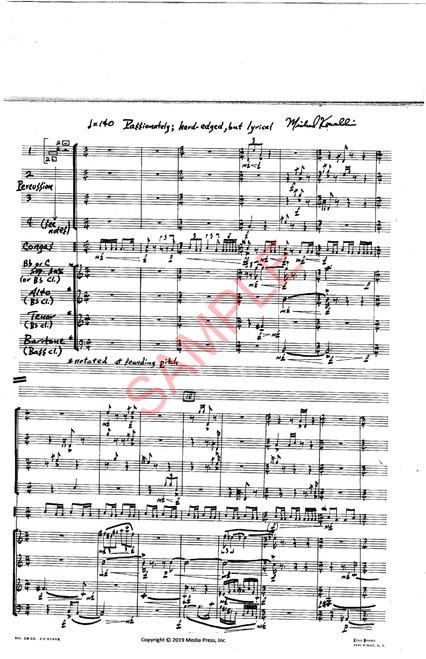

Vapor Trails, a double quartet with congas, was written in 1975 at the University of Illinois and revised in 1981 at the Millay Colony for the Arts. The composition proceeded in three phases. Program one generated musical textures and densities. Program two generated specific pitches, rhythms, and dynamics. In step three the composer extensively revised the output. Vapor Trails pits an ecstatic sax consort against a quartet of stylized drumsets, refereed by a demonically nonstop conga. It's grounded in a kind of statistical tonality in which the aurally rich universe of triadic harmony functions as an acoustic palette, but with as little reference as possible to historical sources in either European art music or American jazz and pop. It's an attempt to be both true to history and to repudiate it. It clearly dates from an early, disreputable phase in the evolution of computer art.

A recording by the University of Michigan Percussion Ensemble and Saxophone Quartet is available on the Einstein Records CD Gringo Blaster and the Equilibrium CD Border Crossing.

Want it now? Click here to purchase a digital copy of this product.

Review from Percussive Notes (2021):

Vapor Trails

Michael Kowalski

“Vapor Trails” is a nearly ten-minute long work by opera composer and computer music pioneer Michael Kowalski. It is written for two quartets and leader, with one of the quartets described as “stylized drum sets” and the other an “ecstatic sax consort,” with clarinets deemed a suitable replacement by the composer. The leader provides a consistent thread of guided improvisation from the conga player, which both establishes the tempo for the piece and provides cues for the quartets. The conga part may be embellished throughout or played as written for players inexperienced with traditional conga drumming.

Kowalski balances the piece by varying space and density, inducing a meditative yet chaotic texture from beginning to end. The quartets are connected temporally through the lead conga player and have little continuity with one another. While each quartet contains shared musical moments, these checkpoints are few and far between; aside from the ending, they do not serve as overt structural markers and come across as incidental simultaneities. The quartets are written polyphonically with non-functional synthetic harmony. As such, they conjure loose audible connections to Western classical music traditions similar to the music of Stockhausen or Donatoni.

Given the lack of typical structure and inconsistent measure number markings between the score and parts, putting this piece together would require extensive score study, as well as patience. For each performer, the individual parts are accessible; however, the independence required to perform in this musical environment given the vague cues will require a mature performer. The conga part will require endurance, familiarity with the instrument, and a good sense of time, as both quartets rely on it to stay together.

While I cannot say I feel favorably about “Vapor Trails” from an aesthetic perspective, the combination of instruments coupled with the emphasis on the non-western drummer as leader provides enough intrigue to warrant its programming on a recital or concert.

—Quintin Mallette