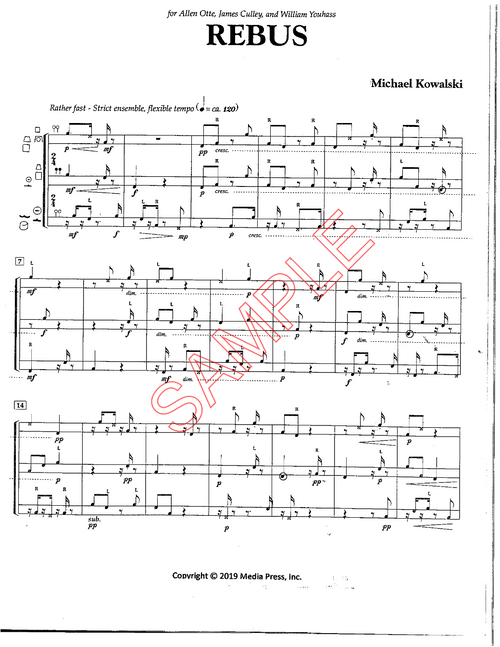

Includes score. Two scores needed for performance.

Print size: 11 x 17"

Double-time

1 movement in four continuous sections. Approximately 15 minutes.

Beyond its obvious debt to Rachmaninoff, early Schoenberg, and bebop, Double-time is, like much of my music from the 70s and 80s, about the overlay of rhythmic maps. The "double-time" of the title thus refers not to tempo but to the relationship between the percussionist's accent scheme and that of the pianist. They may reinforce one another, create a polyrhythm, or contradict one another, and this relationship keeps changing from one section of the music to the next.

A second but by no means secondary concern of mine was the rescue of piano gestures which had been written off as clichés that could no longer be used in non-nostalgic or non-ironic music. This piece might be construed as a test case for how brief, dramatic, tonicizing gestures might be employed against the grain of traditional tonal harmony—a question also posed, at least to my ears, in works by composers such as Salvatore Martirano and Fredric Rzewski.

This double virtuoso work was commissioned by pianist James Avery and percussionist Steve Schick in 1980 and performed by them on tour in Europe and the United States.

Review from Percussive Notes (2022):

This 15-minute duet for piano and multi-percussion takes on several different characters and styles as it progresses through four continuous sections. Paying homage to the melodic/harmonic tendencies of Rachmaninoff and early Schoenberg, and the energy and life of bebop, this piece is contemplative, at times energetic and active, and altogether refreshing as it toggles between music that is rhythmically interlocking and sparsely ethereal.

The ”double-time” of the title refers to the performance relationship between the percussion and piano. Throughout the work, both performers must be adept at serving a supporting role for each other, as well as a role that provides a rhythmic complement to the other player during times of polyrhythmic marriage, and accented punctuations within phrase lines.

Written for pianist James Avery and percussionist Steve Schick in 1980, this piece contains compositional ideas that are fitting for both of those professional performers. Likewise, players who tackle this work will need to perform with mature intentions and techniques to ensure a successful performance. While an audience might not leave the concert hall whistling any melodies from the work, they will have been exposed to art that presents a smattering of musical gestures and ideas not often heard on a “traditional” percussion recital.

—Joshua D. Smith