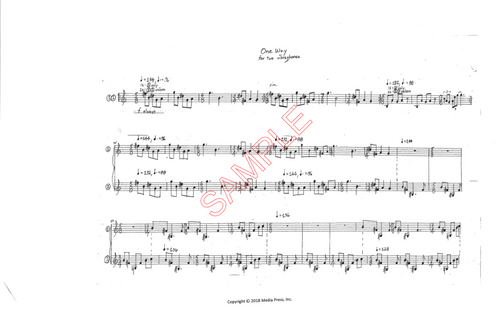

Includes score and instructions.

Print size: Score and Title Page: 11 x 17" Instructions: Letter (8.5 x 11")

Review from Percussive Notes (2021):

Lillian Brook

David Gibson

“Lillian Brook” is a fascinating, if deliberate, exploration of what the vibraphone is capable of achieving from a mechanical standpoint. The score, a whopping 28 oversized pages, which teeters on the border of graphic notation without going in, reads more like a user manual than anything else. Performers are instructed to play as much, or as little, of the score as they choose, in any page order. Within each page is a sequence of two dozen or so harmonic transformations, to be executed gradually along with equally gradual, yet clearly defined, shifts in volume, mallet speed, and vibrato speed (which requires a high degree of constant control over the vibraphone motor’s speed; the composer suggests using a foot pedal and/or digital means to accomplish this).

After wrapping one’s head around the mechanical and technological demands of the piece (not to mention the performance challenges to be confronted), it would be easy to assume that “Lillian Brook” is the product of a post-modern, digitally-versed composer of the 21st Century. Not so! The piece was written in 1973 for Jan Williams, and it went largely undetected until percussionist Aaron Butler presented the work as a part of the “Hidden Gems” Focus Day at PASIC 2018. Having attended his performance, I can attest to the fact that, although an “old” piece by vibraphone standards, “Lillian Brook” will stand out to audiences as beyond bleeding edge. It is remarkable to me that someone was thinking about these kinds of possibilities in 1973, yet these ideas remain largely unexplored today, to the point where this piece’s recent revival will undoubtedly produce a greater impact than its initial presentation half a century ago.

The textures and soundscapes that are produced in any performance will be fascinating, especially if care is taken by the performer to select pages that can form a believable narrative to the audience and allow them to perceive each changing element of this metamorphic piece at a comfortable pace. By the same token, however, there is a real danger in becoming so enamored with the mechanical process that performers may end up plunging audiences into an indulgently overlong realization. One element that I believe is a key to any successful performance is the performer’s willingness to only “sit” on sonorities sparingly, and to use variable transition speeds to build and release narrative tension in a way that the audience will recognize. This piece could easily lapse into a long, Oliveros-esque meditation on each sonority, and while that might be satisfying to some, it will prove difficult for most audiences to accept under normal circumstances.

“Lillian Brook” is an absolute gem that, if given the chance to flourish, could eventually attain icon status within the vibraphone repertoire. For its historical significance alone, college programs should own a copy, but the solo also happens to be entrancing and thought-provoking in its own right. The highest praise I can give is that I look forward to playing it myself.

—Brian Graiser